Bearing Witness to the Holocaust: How the First Video Archive of Holocaust Testimonies Was Established

As the twentieth century draws to a close, we have

witnessed an unprecedented series of geopolitical awakenings. These events

have had both positive and negative sides: the collapse of totalitarian governments

in eastern Europe has been accompanied by the revival of deep religious and ethnic

animosities. It is not a coincidence that during this era of awakenings there

has been renewed attention to the darkest episode of the century, the Holocaust.

Long-silent voices have joined in a steadily growing chorus of testimony that will

continue to be heard when Holocaust survivors--many of them elderly now--are no longer

with us. So compelling has the need to testify become that recent conferences

on the phenomenon of the hidden child--the special case of Jewish children who survived

the Holocaust in hiding--have brought together many hundreds of participants who

were not literally in hiding but have lived with a sense of unbridgeable separation

from their childhoods and their lives both before and during the Holocaust.

This essay is itself the testimony of two such figuratively

hidden children, Dr. Dori Laub and Laurel Fox Vlock. It tells how these two

children of the Holocaust--one an actual survivor, the other growing up in the United

States but keenly aware of events in Europe--grew up on opposite sides of the Atlantic,

established families and careers, and met in New Haven, Connecticut, where they became

the founders of the Holocaust Survivors Film Project, today the Fortunoff Video Archive

for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University. The first undertaking of its

kind, the archive has continued to grow and has inspired similar projects in the

United States and abroad, including a massive program of documentation, Survivors

of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, established by Steven Spielberg.

Efforts to preserve the experiences of victims of the Holocaust

began even as the event itself was unfolding, but for many years they were piecemeal,

gathering the recollections of those who had the fortitude as well as the ability

to write them down. The result was a situation that Dori Laub, a psychiatrist

whose practice included many Holocaust survivors and their children, called "an

event without a witness." What he meant was that not only did the Nazis

try to exterminate the witnesses of their crimes, but the Holocaust was, in its all-encompassing

brutality, incomprehensible and impossible to convey in words alone. A historical gap was thereby

created. It was not until the end of the 1970s, more than thirty years after

the basic facts and the scope of the tragedy became known to the world, that Dr.

Laub and Ms. Vlock had the idea of recording survivors' testimony on video tape.

A historical gap was thereby

created. It was not until the end of the 1970s, more than thirty years after

the basic facts and the scope of the tragedy became known to the world, that Dr.

Laub and Ms. Vlock had the idea of recording survivors' testimony on video tape.

Employing this relatively new technology, they revolutionized

the act of witnessing. Instead of just written or oral accounts, what they

began to gather was a living record of human faces and voices in the throes of remembering,

both the spoken word and what Ms. Vlock called "demeanor evidence."

Such a new way of documenting the Holocaust demanded of them a passionate determination

to overcome pervasive silence, complacency, and fear in hope of gaining acceptance

and support for a monumental task.

What were the childhood experiences that Dori Laub and Laurel

Vlock were reaching back to? What was it that inspired them to start a project

that initially provoked distrust, dismissal, and even irritation yet was destined

to draw out the Holocaust experiences of thousands who might otherwise never have

shared their trauma?

Dori Laub---A Child Survivor from Romania

Dori Laub was a five-year-old boy in June 1942 when he and

his parents were deported from their home in Czernowitz, Romania. For two years

they lived in concentration camps and ghettos in the Romanian-occupied Ukraine.

Dori's father was taken away by German soldiers and never seen again. When

the German army retreated in 1944 from the eastern front, Dori and his mother were

free to return home. Amazingly, they found his grandparents still alive in

Czernowitz. Things were not the same as they had been before, however--the

anti-Semitism unleashed by the deprivations and hostilities of the war was pervasive--and

so Dori emigrated to Israel with his mother and grandparents in 1950. As a

teenager, he developed an interest in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, but an interest

in his own dramatic childhood experiences lay dormant until much later, when recollection

was impelled by crucial events in Israeli history.

The first of these events touched Dori Laub's life

on a brisk morning in 1961. Now a fifth-year student in medical school, he

was walking through a courtyard in downtown Jerusalem on his way to the Hadassah

Hospital. There he saw a group of people waiting in line outside the courtroom

where Adolf Eichmann was being tried for his part in the deportation and murder of

six million Jews. They were waiting to be allowed in to watch the proceedings.

All of Israel had been galvanized by reports from the trial,

and Dori had been listening almost daily to radio reports. There was no television

in Israel in those days, so the man in the glassed-in dock could not be seen.

Dori could only imagine him sitting there, attentively following the arguments through

his earphones.

Dori Laub was most impressed by the eloquence of the prosecutor,

Gideon Hausner, whose voice had a depth and a resonance that seemed to reach far

back into history. He was the authoritative interpreter of events. Dori

also listened to the witnesses but heard them less well and understood them much

less. The acuteness of their pain was driving him away. He could hear

only disembodied fragments, and he could not imagine the people who were talking.

With a shudder, he listened to Eichmann's convoluted reasoning and to the pleas of

his attorney. There was something both impenetrable and shrill in the banality

of the explanations Eichmann gave.

Dori never attended the trial himself, although he was living

in Jerusalem and had a keen interest in it. Somehow, it did not even occur

to him to go. Flashes of his own memories from the days he spent as a child

in the deportation camps came to him, but he did not connect them with the trial.

In fact, he turned his attention away from them. Most of all, he felt the victorious

thrill of the abduction of Eichmann from Argentina by Israeli agents. It was

a stunning feat, similar to a victory in war. The fatal enemy had been subdued

and would pose no further danger. Israel's intelligence and might provided

the safety that he felt was needed. For him, that was enough.

Repossessing a Hidden Childhood

Events in 1967 pushed him a little closer to an engagement

with the past. In June, heavy clouds of war gathered over the Middle East as

Arab armies assembled in full force on the borders of the State of Israel.

The Israeli army lay in trenches waiting. While international bodies made feeble

efforts to prevent the outbreak of war, the threat to Israel's very existence seemed

overwhelming. Dr. Laub was now a resident in psychiatry at Boston City Hospital,

listening to the hourly radio news with a sense of incredulity and regret that he

was so far away.

Then one morning the newscaster reported that 80 percent

of the Arab planes had been destroyed on the ground by a surprise Israeli attack.

The war had begun, and Israel was already in complete control of the skies.

An atmosphere of relief, freedom, and rejoicing prevailed in Israel. Together

with a friend who was an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Laub bought a sleeping bag and high-top

boots and presented himself at the Israeli consulate in Boston. Throngs of

people were there, all trying to get passage to Israel. The friend was chosen

to go because of his specialty; Dr. Laub was sent home. The war was over in

six days; Israel had expanded borders and a future that held all the potential and

promises one could imagine. The nightmare of abandonment, helplessness, and

destruction was only brief, banished by the might of the Israeli air force.

Dr. Laub continued his psychoanalytic training in 1969 at

a small hospital in a village in Massachusetts. During the first week of his

own analysis, he talked of beautiful childhood summers spent at camp, meadows, blue

skies, a river, and a little girl sitting by him on the bank of the river, trying

to convince him that you could eat handfuls of grass and not be hungry. What

could have been more pastoral than that? But the camp was Cariera de Piatra,

"the stone quarry," to which Jews from the northeastern provinces of Romania

had been deported by the tens of thousands in June 1942, and from which they would

be ferried across the Bug River to the German-occupied Ukraine, there to be executed

by soldiers of the notorious Einsatzgruppen. This hardly existed in Dr. Laub's

memory. The analyst interrupted at this point and said that he himself had

a story to tell. He had been a member of the Swedish Red Cross team that entered

the concentration camp of Theresienstadt after liberation in 1945 and interviewed

many of the survivors. Some women, he said, declared under oath that conditions

in the camp were so good that they were brought breakfast in bed every morning by

SS officers.

There could not have been a more potent interpretation of

Dr. Laub's denial and what had happened to him. He had not wanted to remember.

Now he dropped the stories of summer camp. He abandoned his forgetfulness.

Yes, the river was mysterious. And he knew even then that death must take place on the other side.

Although he had remembered it as being about a kilometer from the camp, in reality

it was only a hundred yards away. People were sleeping on the floor, thirty

to forty to a room, whole families--men, women, and children--together. The

sick, the crazed, and the bewildered were shuffling around in rags, begging for food.

He could remember seeing them scavenging in the garbage and wolfing potato peels.

One man was being flogged. Afterward, his back streaked with blood, the man

was sitting and smoking a cigarette. Dr. Laub remembered walking up to him

but remaining silent. He had wanted to ask the man what it was like.

And he knew even then that death must take place on the other side.

Although he had remembered it as being about a kilometer from the camp, in reality

it was only a hundred yards away. People were sleeping on the floor, thirty

to forty to a room, whole families--men, women, and children--together. The

sick, the crazed, and the bewildered were shuffling around in rags, begging for food.

He could remember seeing them scavenging in the garbage and wolfing potato peels.

One man was being flogged. Afterward, his back streaked with blood, the man

was sitting and smoking a cigarette. Dr. Laub remembered walking up to him

but remaining silent. He had wanted to ask the man what it was like.

The figure of his mother was at the core of Dr. Laub's memories

as someone whose relentless battle for life made his surroundings seem safe.

His father was an adored and revered figure, but a dreamer who believed in justice

and a god who existed at the end of the universe of stars he and Dori would look

at during their nightly walks outside the camp barracks. Besides, Churchill,

Roosevelt, and other world leaders would not let them come to harm. His father

also believed that if the Jews held together, followed orders, worked hard, and proved

themselves, they would be rewarded and the Germans' promises of decent housing and

a better life would be kept.

The Language of a Different World

Dr. Laub's mother, on the other hand, believed only what

was within her power. As the train pulled away from Czernowitz, people in the

cattle car were crying. Dori didn't know what they were crying about, but he

knew it was something terribly sad, so he began crying too. When his mother

asked him why he was crying, he answered that it was for his little brass bed, where

he would say his nightly prayers. His mother told him that she had two coats,

one of which she would sell on their arrival at the camp to buy him a new brass bed.

Dori stopped crying.

Later, when SS officers asked for volunteers to cross the

Bug, promising good working conditions, food, and housing, his mother refused to

join them. She did not believe one word of what the Germans said, having a

clear vision of what was really taking place. Dr. Laub remembered grim fights

between his parents when his father wanted to present himself with other men for

transfer. Once his mother threw a boot at his father, who retreated to their

room to hide. Those who did present themselves were taken away and never returned.

It all culminated one October morning when the inmates

of the camp were assembled in a central square and arranged in groups for the German

trucks to transport them across the Bug. There was something feverish going

on, with an expectation of the unknown. Dori had hardly slept the night before,

disturbed by the sound of trucks. Suddenly a lawyer, who had been making a

list of people that had a certain amount of money--Dori's family was not among them--picked

up his suitcase and began running. When Dori's mother asked him where he was

going, he replied, "To a place where you do not belong." Dori's mother grabbed Dori's

hand, picked up her suitcase, and said, "Where you go, I'll go."

Dori's father was reluctant to go along. He was the leader of a group of thirty

people. He could not leave them behind. Only after Dori's mother threatened

to leave him did he join her and Dori. The three ran about half a mile to the

outskirts of the camp, to a house that was completely boarded up. Dori's mother

knocked at the door. There was no response. Then she yelled, "If

you don't let us in, I'll turn you over to the Germans." The door opened,

and Dori and his parents found the house crowded with people. These were the

"specialists," who had bribed the Romanian commander of the camp to say

that he needed them to maintain the grounds and therefore they should not be taken

across the river. As the day progressed, shooting and screams could be heard.

At one point, a German patrol stopped outside the house and shouted, "Juden

heraus!" Husbands and wives said good-bye to each other and exchanged

possessions. Dori's father gave his mother his wristwatch. Luckily, the

Romanian commander was reached and managed to convince the Germans that they should

leave this group alone. When Dori's family and the others left the house that

evening, they found the whole camp deserted.

Dori's mother grabbed Dori's

hand, picked up her suitcase, and said, "Where you go, I'll go."

Dori's father was reluctant to go along. He was the leader of a group of thirty

people. He could not leave them behind. Only after Dori's mother threatened

to leave him did he join her and Dori. The three ran about half a mile to the

outskirts of the camp, to a house that was completely boarded up. Dori's mother

knocked at the door. There was no response. Then she yelled, "If

you don't let us in, I'll turn you over to the Germans." The door opened,

and Dori and his parents found the house crowded with people. These were the

"specialists," who had bribed the Romanian commander of the camp to say

that he needed them to maintain the grounds and therefore they should not be taken

across the river. As the day progressed, shooting and screams could be heard.

At one point, a German patrol stopped outside the house and shouted, "Juden

heraus!" Husbands and wives said good-bye to each other and exchanged

possessions. Dori's father gave his mother his wristwatch. Luckily, the

Romanian commander was reached and managed to convince the Germans that they should

leave this group alone. When Dori's family and the others left the house that

evening, they found the whole camp deserted.

Dr. Laub's mother had an uncanny ability to see the

stark untainted truth and act accordingly, to know the language of what was really

a different world, a world of sardonic deception and killing, and to avoid the comforting

illusion of the continuance of the world they had known and loved. Learning

the other language was crucial for physical and psychological survival. It

was through familiarity with the verbal and nonverbal vocabulary of the concentration

camps that one could detect the signs of danger. Being able to understand,

speak, and act in that other language meant staying in touch with the truth in spite

of overwhelming inner temptations and external deceptions that enticed one to succumb

to the illusion of the sameness of the two worlds. In spite of its disintegrating

effect, separating the two worlds was the only way to maintain sanity. Only

through separation could either remain true.

Probing Psychological Aftereffects of the Holocaust

Thus Dori Laub repossessed his hidden childhood.

But it was not until he encountered Holocaust survivors' children in the Israeli

army during the Yom Kippur War of 1973 that Dr. Laub began to explore systematically

the psychological aftereffects of the Holocaust in others and in himself. By

now affiliated with Yale University, he followed the outbreak of hostilities over

the radio. News was scant in the first couple of days, and at his synagogue

there did not seem to be a lot of interest in it. The detachment and silence

were worrisome. Then the disturbing news became clearer: Arab armies

had overrun the Barlev line on the Suez Canal and were pouring in through the Golan

Heights. Dr. Laub eagerly waited to hear of an Israeli counterattack, but those

that were mentioned had failed. Moreover, the Israeli air force had lost 20

percent of its planes. This time the Soviet missiles were effective.

All the safety he had experienced or imagined through the invincibility of the air

force seemed to have vanished. This was not a war like other wars Israel had faced. Dr.

Laub had to be there for whatever fate would bring, and so he left his young family

behind.

This was not a war like other wars Israel had faced. Dr.

Laub had to be there for whatever fate would bring, and so he left his young family

behind.

All through the flight to Israel, there was a restlessness.

A number of religious Jews prayed, and children and whole families milled around

in the aisles. As the plane flew over the eastern Mediterranean, everyone became

silent and apprehensive. What if Arab fighter planes intercepted them and shot

them down? Would there be an Israeli escort to bring them in safely?

There was none in sight, but the landing was without incident. In fact, the

arrival took place in a sort of vacuum. The airport looked deserted.

A few elderly men in military uniforms walked apathetically around. Nobody

was in a rush. The action was somewhere else, and the arrival of a plane from

abroad was not of much consequence or interest. Police and customs officials

seemed preoccupied and uninvolved in their work. It seemed to Dr. Laub as though

everyone had already given up and submitted to the inevitable without so much as

a protest.

On October 10, Dr. Laub was one of the psychiatrists at a military installation receiving

casualties from the Syrian front, the lightly wounded and those who had fallen apart

psychologically on the battlefield. There were only a few in the beginning,

but within days there were hundreds--bewildered, dazed, walking around aimlessly

or lying in a stupor. Their eyes spoke of something indescribable. Many

were crying for friends whom they had seen killed. Dr. Laub listened to their

accounts, felt some of their terror and grief, and saw most of them pull themselves

together to return to the front line. But some of the soldiers who had become

psychological casualties on the battlefield did not improve. Their abysmal

terror and bleak grief continued unabated. Life around them did not matter;

they were captivated by something else with a life of its own taking place inside

them.

Piecing Past and Present Together

Dr. Laub gradually came to realize that these were mostly

children of Holocaust survivors. One young man in his mid-twenties, a married

man whose wife was expecting a baby, lay there with wide-open eyes, unresponsive,

running for cover under a bed and screaming when there was a loud noise. He

had been a radio operator at a refueling station where tanks stopped for ammunition

and gasoline on the way to the front. He saw the crews and their commanders

and then followed their voices on the radio. He heard descriptions of the battles,

orders given, and frequently the last words spoken, followed by silence. He

knew of something terrible that was happening at another place without being able

to intervene or stop it from happening. He had heard of his parents' experiences

in the Holocaust in a similar way; with them too he was a passionately involved yet

completely helpless listener who could do nothing to stop events from happening.

This was the story that Dr. Laub pieced together after days of listening to the soldier's

mumbling, and when he finally knew enough to retell it to him, the soldier came out

of his stupor, but without an identity, without a name, and without a memory of his

wife's name. He had lived in a condensed way and with utter immediacy what

his life with his family had been all about, but this time he had had to listen to

the radio and be a helpless witness to the end, something he could avoid with his

parents by closing off his imagination when their story became too threatening.

What he experienced now could not be relegated to another place or time, nor was

there any question about the reality of the event. When he returned to the

living and haltingly began to know again who he was, he named his newborn son after

one of the tank commanders whose last orders he had listened to before the radio

transmission went dead.

Another man, about twenty years old, became disorganized

and violent, had hallucinations, and played the clown, trying to entertain the whole

camp. As a military policeman, he had watched mangled bodies being returned

from the battlefield, including the occupants of a civilian car that he had tried

without success to stop from driving toward the front. The young policeman

had subsequently hit a Syrian prisoner of war in the face with his boot. Between

fits of deranged behavior, he told Dr. Laub his story. His father was a survivor

of Auschwitz, who would talk of seeing the SS men smash his baby against a wall.

The young man's parents had divorced, and his stepmother tried to get rid of him

by locking him out of the house. The psychological wounds of his childhood

had never healed. When he was faced with the brutality of war and especially

when he had compelling evidence of such brutality within himself, it was all too

real for him and uncontainable. Nothing Dr. Laub did was of any help to him,

and he was eventually transferred to a regular hospital for extended treatment.

By now Dori Laub had come face to face with atrocity--its

persistence in memory and its unrelenting impact. This seminal observation

of the way in which the Holocaust lives on even in the lives of children of its victims

led him to draft a proposal for a research grant. The results were disappointing:

in answer to nearly a hundred submissions, he received only one response expressing

interest, from a German research institution. This later gave him the opportunity

to work extensively with survivors living in Germany, but his hope to pursue the

study waned. He was forced to conclude that there was not much interest in

the Holocaust. Not until his fortuitous meeting with Laurel Vlock in 1979 did

he find a way to test his ideas and develop new ones. It was the collaborative

efforts of these two very different people that brought the video archive into being.

Laurel Vlock---Growing up Jewish in America during the Holocaust

Unlike Dori Laub, Laurel Vlock has been an American from birth,

growing up in New Haven in a predominantly non-Jewish middle-class neighborhood.

From an early age, she was aware of being "other," experiencing discrimination

on several levels at the public elementary school: initially and repeatedly

singled out by a kindergarten teacher for having a "fancy" given name and

then by playmates for being Jewish and nearsighted. Catholic peers boasted

that the imposing Catholic church that dominated the neighborhood was out of bounds

for her, and the nuns who lived in a separate building only two doors from her home

pointedly ignored her when greeting other children. Ms. Vlock and her younger

sister both vividly remember being called "Christ killers." Patient

explanations at home that Jesus was Jewish too and was crucified by the Romans, not

the Jews, did little to relieve Laurel's anxieties.

The sense of being an outsider pursued her in the fall of

1936. National elections pitted Governor Alf Landon of Kansas against President

Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The sidewalks leading to the elementary school were

covered with slogans, some simply supporting Landon with the sunflower symbol, others

quite vicious anti-FDR scrawling--even suggesting that FDR was really Jewish.

All the political activity had only one message for Laurel: her parents, and

by extension she, were on the other side from her playmates and their families.

Her house had National Recovery Administration stickers on the window, along with

other evidence that her parents were Democratic party supporters, out of step in

a largely Republican neighborhood.

Ms. Vlock remembers this period of her life with mixed emotions

about relations with neighbors and friends. Her parents, always alert to signs

of anti-Semitism, indicated a deep ambivalence. While they showed respect and

friendliness toward gentile acquaintances, they also expressed, in the privacy of

their home, suspicion about how much one could count on non-Jews.

Experiences in Europe on the Brink of War

The Fox household was the scene of several family get-togethers

to hear about the experiences of two bachelor uncles who had traveled widely and

gave exciting descriptions of their adventures, always remembering their young nieces

with special gifts. One particular report in the mid-1930s had disturbing elements

that left an indelible impression on the family. It involved both the sinister

atmosphere of anti-Semitism in Germany and the plight of cousins living in the Soviet

Union. One of the uncles had spent the summer of 1936 touring Europe, concluding

his trip with a visit to a small shtetl on the outskirts of Odessa called Otchakoff,

from which Laurel's grandparents had emigrated in the early 1880s. Finding

family members living there in desperate poverty, he gave them everything he had,

returning to America with only the clothes he was wearing: a shirt, trousers,

and a pair of shoes--no socks or even, so the family story went, underwear.

To his impressionable young niece, this story was haunting.

The uncle's summer excursion precipitated a major event

in Laurel's early years. He insisted that his sister accept his offer to pay

for a transatlantic voyage for the family the following summer so that the girls

could see Europe as they might never see it again. It would also, he pointed

out, be an opportunity for Rose Fox to visit their much older sister, Anna Phillip,

and her family, who lived outside London. Thus Rose and her daughters sailed

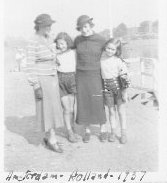

for England aboard the Queen Mary in late June. The itinerary included a long

stay in England and travel in France, Belgium, and Holland.

In England, Laurel and her mother and sister were

disturbed to see evidence of anti-Semitism. Oswald Mosley, a fascist and Nazi

sympathizer, was conducting a virulent anti-Semitic campaign on billboards and posters

in the London underground. Caricatures of Jews were everywhere on the walls

of the transit system. Often the ugly drawings depicted Jews with glasses,

suggesting inferiority, which was particularly distressful to an already self-conscious

young girl. The graffiti and Mosely's demagogic harangues in Hyde Park were

the subject of considerable disagreement between Laurel's mother and her English

relatives, who dismissed the "aggravations" as representing only a minority

point of view.

Several experiences on the continent proved even more intimidating.

In Brussels, Rose had become friendly with two English women, who invited seven-year-old

Marian to accompany them to a sweetshop while Rose attended to other matters with

Laurel. As Marian reported when she returned, the two ladies stopped by a store displaying

a picture of Adolf Hitler in a fancy silver frame. Marian became alarmed when

the women commented that Hitler was a "wonderful man." She felt trapped;

she knew she could not find her way back to the hotel by herself, and she was now

afraid of these new "friends." When one of them later asked her what

her religion was, she immediately responded, "Catholic," which, she was

relieved to see, pleased the two ladies. After hearing about Marian's scary

experience, Laurel felt anger, admiration, and guilt: anger at the supposedly

nice ladies who admired Hitler; admiration that her little sister had the presence

of mind to protect herself; and guilt about her sister's untruthfulness.

As Marian reported when she returned, the two ladies stopped by a store displaying

a picture of Adolf Hitler in a fancy silver frame. Marian became alarmed when

the women commented that Hitler was a "wonderful man." She felt trapped;

she knew she could not find her way back to the hotel by herself, and she was now

afraid of these new "friends." When one of them later asked her what

her religion was, she immediately responded, "Catholic," which, she was

relieved to see, pleased the two ladies. After hearing about Marian's scary

experience, Laurel felt anger, admiration, and guilt: anger at the supposedly

nice ladies who admired Hitler; admiration that her little sister had the presence

of mind to protect herself; and guilt about her sister's untruthfulness.

Crossing the Bridge into Hitler's Germany

Another experience developed into something more threatening,

indeed terrifying. In planning their tour on the continent, it was arranged

that they would join their aunt and uncle at the Spa in Mondorf, Luxembourg. Aunt Anna's

husband, born and raised in Germany, had brothers who had been decorated for heroism

in the German army in the Great War. Both Anna and Morris Phillip were comfortable

with German people and felt that reports of German anti-Semitism were grossly exaggerated.

After a few days at the Spa, Aunt Anna suggested the two women and the girls take

a day's sight-seeing trip to Remich, where they would see the historic bridge that

the German army had used to invade Luxembourg and Belgium some twenty years earlier.

It was to be an educational experience.

Aunt Anna's

husband, born and raised in Germany, had brothers who had been decorated for heroism

in the German army in the Great War. Both Anna and Morris Phillip were comfortable

with German people and felt that reports of German anti-Semitism were grossly exaggerated.

After a few days at the Spa, Aunt Anna suggested the two women and the girls take

a day's sight-seeing trip to Remich, where they would see the historic bridge that

the German army had used to invade Luxembourg and Belgium some twenty years earlier.

It was to be an educational experience.

As they approached the bridge, however, Aunt Anna pressed

Rose to let her take the family across into Germany so her young nieces could glimpse

the beauty of the German countryside. It would be a shame, she said, to come

all the way to Europe and not even set foot in Germany. Laurel's mother was

hesitant; they had no visas for Germany. But Anna insisted that hers would

cover all of them. Besides, the names Fox and Phillip did not sound at all

Jewish, so that was not a worry.

The German border guards had a very threatening appearance, quite unlike that of

any other policemen she had seen, dressed in black uniforms, high black boots, and

stiff peaked caps with what appeared to be a skull and crossbones above the visor.

Two guards sat on shiny black motorcycles, and two others held growling German shepherds

on leashes. Aunt Anna showed the guards her German visa and all their passports

and, in fluent German, persuaded them to let her take her visaless American relatives

for an hour's walk in Germany.

Ms. Vlock's memories of that short excursion are very graphic.

It was close to lunch time and the sun was very hot, and she wondered how those mean-looking

German border guards could wear their dark, heavy uniforms on such a warm day, especially

since the little guard house was not shaded by a single tree. She and Marian

were wearing their usual travel clothes, camp shorts and white blouses, and their

mother and aunt were also in light summer clothes. After walking a short distance

on the dusty rural road, they began to be thirsty. In a field alongside the

road, three children were playing. When they saw the four pedestrians, they

stopped and gave the Nazi salute, arms raised straight out in front, and yelled,

"Heil Hitler." Laurel and Marian exchanged looks at this unpleasant

reminder of where they were.

Aunt Anna spotted a wayside inn, where they stopped for

a drink. It was very dark and pleasantly cool inside, and it took a while to

see the room clearly after coming from the bright sunlight. Ms. Vlock remembers

a long bar of dark wood and several men sitting on stools. Laurel and her mother,

sister, and aunt were seated in a booth across from the bar. A waiter came

over, and Aunt Anna asked for four Coca Colas. When the drinks came, to Rose

and Anna's astonishment the waiter asked for four American dollars. Rose was

upset at this exorbitant charge, and Anna admitted that the inn was taking advantage

of Americans but said they shouldn't make a fuss. They hadn't taken more than

a few sips when Marian pointed to two larger-than-life portraits of Hitler and Goering

hanging above the bar and stuck out her tongue. Rose and Anna whispered that

they hoped no one had noticed and, without allowing the girls to either finish their

expensive drinks or take them along, hustled them out of the inn and began walking

rapidly back toward the border. They were walking so fast and so deliberately

that this time the children playing by the road just stood and stared at them.

Laurel later conceived other more terrifying images from listening to her mother's

angry speculations about what might have happened had they been detained and identified

as Jews. (The experience was so affecting that forty-one years later in 1978,

during a European vacation with her husband and daughter, Ms. Vlock insisted on showing

them the Spa in Mondorf and the bridge in Remich, retracing the route right up to

the door of the inn, which was still in business.)

Back home in the United States in the late 1930s, there was also

ample evidence of anti-Semitism. Laurel's parents were alarmed by the radio

demagogue Father Coughlin and his companion in anti-Semitic fervor, Gerald K. Smith.

By the spring of 1939, there was even more awareness in the Fox household of the

plight of European Jewry, as the refrain "No one wants the Jews" was dramatically

demonstrated by the voyage of a ship called the St. Louis. That boat, with

its cargo of Jews trapped on it, took on enormous proportions for Rose and John Fox,

who were in a frenzy of activity, sending telegrams, writing letters, and talking

on the telephone constantly, to whom, Laurel did not know. What she did know

was that all the efforts to find a country in the Americas that would accept the

Jews on the St. Louis were of no use, and her parents were extremely upset.

The tense atmosphere in the Fox household and the preoccupation

with the fate of the Jews just before and during the war years had a considerable

effect on Laurel's relations with peers in high school. Breakfast-time radio

reports, followed by anguished discussion and speculation, set the tone for the day.

Joining friends on the walk to school, it was difficult for Laurel to participate

in the usual teenage banter when her head was full of images of war-torn Europe and

what was happening to the Jews.

The atmosphere became more charged when Laurel's mother,

distraught over a story on the news about a tragedy that had befallen a group of

Jewish girls in Poland in the early spring of 1943, prevailed on Laurel to have her

invited to a meeting of Laurel's high school sorority, Pi Epsilon Pi. The agenda

for the meeting included plans for using the group's treasury for a dance.

Sororities and fraternities being strictly segregated, all the Pi Ep girls were Jewish.

At the meeting, Rose Fox dramatically told how ninety Jewish girls at a boarding

school in Poland had been ordered to "prepare" themselves for a "visit"

by German officers. Knowing what this meant, all of the ninety took lethal

doses of poison rather than submit. When the German officers arrived, they

found their reception marred and immediately shot and killed the school administrators

and teachers.

This tragedy, which was revealed as reports of Hitler's

Final Solution were starting to appear in the war news, so impressed and horrified

the sorority members that they unanimously voted to forgo the dance and send all

the money in the treasury to organizations trying to save Jewish children in Nazi-dominated

Europe. Laurel was proud of her mother and of the reaction of her peers, but

she was also made painfully aware of her otherness by the response of some parents,

who protested that their daughters' innocent pleasures were being denied by the introduction

into their young lives of an unhealthy preoccupation with distant, nightmarish events.

Heated discussions followed in which these parents declared that Laurel and her mother

had no right to push their ideas on others.

When she became a student at Cornell University in the

fall of 1944, Laurel found her own inner motivation for activism, which was triggered

by the housing situation at the university. It was the first of several indications

that prejudice toward Jews was to be found even at an institution like Cornell, in

those days the only fully coeducational Ivy League school. No religious or

ethnic identification had been asked for on the application forms, yet when Laurel

arrived on campus, she found herself assigned to a six-person dormitory suite with

five other Jewish women--the only Jews in the entire dormitory complex, which housed

a hundred women. This obvious segregation perplexed and annoyed all six women.

Only three had names that sounded Jewish: Altman, Marks, and Reinhardt.

The other three were Daniels, Fox, and Topkins. On what basis did the university

make the residence assignments? And how was it that Catholic women were also

assigned to all-Catholic suites? This demeaning segregation was obviously imposed

by design.

Laurel subsequently joined a college sorority, where her

preoccupation with the plight of the Jews after the Allied victory and the opening

of the concentration camps set her apart once again. This concern became a

determination to understand the history of the Jewish people and help realize their

destiny. She spent the summer of 1946 at the Brandeis Camp Institute, a Zionist-oriented

youth retreat attended by two representatives from each U.S. state. The war

was now over, and emanating from Palestine was a movement to gather the remnants

of European Jewry and reestablish the Jewish nation, Israel. It was an intense

experience of training in Jewish history and culture in a kibbutz-like environment,

and Laurel loved it. The age-old persecution of Jews in the diaspora was presented

as a rationale for the philosophy of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism,

who maintained that wherever Jews were a minority, they were bound to suffer intolerance.

The remedy for this ineluctable discrimination, which culminated in the Nazi atrocities,

was a home for the Jews in the land from which they had been expelled some two thousand

years before, but had never forgotten. The program at the Brandeis Camp Institute

fostered a utopian Zionism, a dream of creating an exemplary society in Palestine,

in which Jews would experience a cultural, spiritual, national, and physical rebirth,

fulfilling their biblical destiny of being "a light unto the nations."

It would also be a place where, in the post-Holocaust era, persecuted Jews would

find a haven, protected by their own government and army, living like normal people

in their own nation.

The experience strengthened Laurel's determination to raise

the social and political consciousness of her fellow students, and once again, this

time deliberately, she set herself apart from campus social life by becoming an activist

for the Zionist cause. For a time after the partition of Palestine in 1947,

she seriously considered helping build the Jewish homeland by joining a kibbutz.

Her idea never materialized, however, and after graduating in 1948, Laurel married

and began raising a family in the New Haven area.

Probing the Holocaust in Broadcast Journalism

The early 1960s were full of optimism about social change,

and with all her children now at school for the better part of the day, Laurel Vlock

became involved in community activities, a course that made her aware of the power

of the broadcast media to focus on issues and shape attitudes. She began a

new career by persuading the Yale Broadcasting Company to let her produce educational

and public service radio programs for the greater New Haven community. This

led to producing television shows and films and soon to hosting a television series

that explored significant social issues.

One daunting assignment in 1978 was to produce a program on the commemoration of

Yom Hashoah (Day of Holocaust Remembrance) in New Haven. To give the documentary

a narrative thread, she videotaped an extended interview with one of the commemoration's

featured speakers, the author and Holocaust survivor Jerzy Kosinski. For Ms.

Vlock, the power of personal testimony of survival, captured visually during the

interview, was a revelation.

At a luncheon in February 1979 celebrating awards that the documentary had won, the

managers of the television station encouraged Ms. Vlock to do something more--"something

different"--on the Holocaust. This was indeed a welcome opportunity, but

the timing was a problem. It was some six months after the documentary had

aired, and during that time NBC had presented the dramatic miniseries Holocaust.

Although there was much controversy in the press about the appropriateness of fictionalizing

the subject, the impact of the series on public consciousness around the world was

profound. In addition, a French documentary film, The Sorrow and the Pity,

which had been showing in movie theaters around the country, had provided a different

perspective on the victims and the social environment in which they were victimized.

What more could be done?

Ms. Vlock discussed her predicament with a colleague and

an independent producer. The idea surfaced that if she could tape survivor

testimonies in a less intimidating setting than a television studio, she might accumulate

enough material to prepare another documentary. This seemed a reasonable possibility,

since television recording equipment had recently become more portable.

Making further inquiries on the subject, she was told about

a Holocaust survivor in the community who was a practicing psychiatrist: Dr.

Dori Laub. Perhaps she could begin by interviewing him on camera. She

made an appointment to see him. Thus Dori Laub and Laurel Vlock met for the

first time. Both had had childhood experiences of the Holocaust--in one case

direct, in the other indirect--that were recovered after years of successful work

in psychiatry and broadcast journalism, and both had begun to examine the effects

of the Holocaust on its victims, but the project they were to undertake together

could have been done by neither alone.

As they talked and Ms. Vlock explained the new, more flexible

conditions for videotaping, Dr. Laub stated his opinion that interviewing just one

person or a few people would be a token act and that what was needed was a film built

on many interviews that could begin telling the story. He revealed to her that

there were scores of survivors in New Haven who had preserved a public and perhaps

even a private silence but who might be ready to talk about their previous lives

if they were approached in the right way. Because this would be an independent,

experimental effort, the two of them would have to fund it themselves.

The First Videotaped Interviews of Holocaust Survivors

Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock made no specific plans at this first

meeting, but they had several telephone conversations over the next few months.

Then, at the end of April, Ms. Vlock "suddenly," as Dr. Laub remembers

it, called to tell him that she had a film crew available for an evening that week,

May 2, and if he could find survivors who would participate, they could begin.

Dr. Laub called two survivor friends and another survivor who was active in the Jewish

community and was able to secure the commitment of four people to come and be interviewed.

The taping session took place in Dr. Laub's office

at the end of a regular working day. Food and drink were prepared for those

who might arrive before the previous interview was finished, as neither Dr. Laub

nor Ms. Vlock was able to anticipate how long each person might want to talk.

The camera crew arrived and began setting up its equipment. The office furniture

was rearranged, and the first survivor witness was positioned facing the camera with

Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock flanking it so that the survivor would be talking both into

the lens and to the two interviewers.

Dori Laub and Laurel Vlock had never worked together before,

and their styles were different to begin with, hers being that of a journalist and

his that of a psychoanalyst. In spite of that, when the first testimony began,

everything fell into place, because the power of the testimony silenced their differences.

Everyone in the room was transported to another time and place, a setting that had

been waiting untouched and unchanged for many years behind locked doors. No

one, including the witnesses themselves, knew beforehand what the testimonies would

contain; experiences and reflections came out from recesses of memory that the witnesses

did not even know they had. Individuals that Ms. Vlock had thought of as ordinary

members of the community were now revealing large areas of themselves and of their

pasts that had been buried for many years. These were people who, as happened

in the cases of many survivors, had engaged in almost overly full lives in response

to an intense desire to recreate shattered families and careers.

One man, now a successful baker in New Haven, spoke with

shame about being so hungry that he stole a slice of bread from his sister's ration.

A woman spoke of the utter humiliation of having to run naked through a line of German

soldiers at Auschwitz. A third survivor spoke of feeling like an animal in

a cage. She tried to imagine what passengers might be thinking as they looked

out the windows of trains passing the labor camp. As if she were sitting on

a fence, she felt that she no longer knew where she belonged. The fourth, after

telling about her impossible and terrifying duty to warn her deaf parents and younger

sister to hide during Gestapo roundups, asserted that she could not, nor did she

want to, reconcile her two lives, that they needed to be kept apart to retain their

integrity.

The interviews lasted until the early hours of the morning,

producing more than four hours of taped material, but no one objected or complained.

By that time, Dori Laub and Laurel Vlock knew that they had found something unexpected,

something the like of which they had not seen before, and they knew they needed to

continue. They were determined to videotape as many survivors as possible in

order to create an unvarnished record from individual, unique perspectives of this

most horrific of tragedies.

Overcoming Formidable Obstacles

Before this project could be undertaken, however, several formidable

obstacles--technical as well as nontechnical--had to be overcome. The technical

difficulties were attributable to the fact that portable videotaping was a relatively

new technology in the late 1970s. Portable recorders, used primarily for so-called

electronic news gathering, accommodated only twenty-minute cassettes, and changing

the tape every twenty minutes compromised the flow of thought and expression.

(Film, by contrast, with its ten-minute magazines that had to be changed in a dark

room or light-impervious black bag, would have been unmanageable altogether for this

experimental project.) However, rapid developments in the industry were allowing

greater flexibility, and cameras were becoming smaller and quieter and thus could

be unobtrusive recorders of a survivor's testimony. Their portability meant

that taping could be carried on in any familiar or comfortable setting; no intimidating

studio situation was necessary. Thanks to the reduced costs of the new medium,

the project had the potential to include thousands of Holocaust victims and witnesses,

although finding financial support beyond their own resources was at first a troublesome

problem for Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock.

Most formidable of the nontechnical problems was the general

reluctance of survivors to talk at length about their ordeals. As a psychoanalyst

and a survivor himself, Dori Laub understood their deep ambivalence. On the

one hand, survivors felt a need to bear witness, to be heard by empathetic listeners

and to exorcise the ghosts of the past. But at the same time, there was an

even stronger feeling that the past could not be mended and that one's experiences

were too terrible to reveal even to willing listeners. This past was a present

reality for many, like the woman who saw the faces of camp inmates in the strands

of her shag carpet.

A fear that fate would strike again was central to the memory

of their trauma and their inability to talk about it. The trauma was an event

outside normal reality, with no beginning and no end, and thus ever present and unmasterable.

And so the imperative to tell was inhibited by the impossibility of telling.

Even if it were possible to tell, those willing to hear might be simply curious or,

worse still, might take a certain grotesque pleasure in the revelations of human

degradation and suffering. Far from providing a catharsis or healing their

deep psychological wounds, relating their experiences might, they feared, simply

revive the horror--as for some it did.

A lesser, but nonetheless discouraging, obstacle was the

early reluctance of leaders of the Jewish community to accept the project.

They were hesitant to turn from current concerns to what they felt was an unproductive

dwelling on the past. Projects to build Israel were at the top of their agendas,

and this new retrospective project would only distract people, perhaps siphoning

off scarce funding and, even worse, undermining the self-confidence of Jews in the

United States and Israel by reflecting on the Jew as victim.

Reaching Out into the Jewish Community

An important psychological and financial breakthrough

came on June 3, 1979, when Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock spoke to a group of survivors in

New Haven, members of a labor Zionist organization, the Farband. Moved by the

presentation, the Farband members pledged a contribution of two thousand dollars

as well as their participation as witnesses. The president of the Farband,

William Rosenberg, became a director of the Holocaust Survivors Film Project in August,

when it was formally established as an organization. Mr. Rosenberg's comments

reflected a new survivor sentiment: "Now we recognize our duty to tell

the full story, however painful, and this project provides the help and encouragement

the survivors need to come forward . . . after thirty years of silence."

The silence that had been both a trap and a sanctuary for many survivors was about

to be broken.

Reinvigorated by the backing of the Farband members, Ms.

Vlock and Dr. Laub decided to seek wider recognition for what they hoped would become

a large and ambitious effort. The first step was to use the pledged money to

edit the four hours of tape into a half-hour tape that could be shown to others as

an example of the project. They could then call a press conference and enlist

the support of a broad cross section of community leaders for a public launching

of the project.

The press conference was held at Mr. Rosenberg's home on June 28. The project's

stated goal was to record the testimony of the more than two hundred survivors in

the New Haven area. Pledging support to the effort were New Haven city officials

and community leaders as well as a representative of the President's Commission on

the Holocaust, Michael Berenbaum. The commission had been established by President

Jimmy Carter to "harness the outrage of our memories to banish oppression from

the world." A statement from the commission's director, Rabbi Irving "Yitz"

Greenberg, said in part, "We hail the beginning of the pioneering project in

New Haven to videotape and record the testimony of survivors. It offers a unique

vehicle to communicate the reality of the Holocaust and the dignity and life of the

victims--a vehicle which can become a national model." It was announced

at the press conference that twelve thousand dollars had been raised after showings

of the edited version of the four interviews.

Coverage of the press conference in the New York Times precipitated

a dialogue between Ms. Vlock and President A. Bartlett Giamatti of Yale University,

who expressed enthusiasm for the initiative and an interest in Yale's involvement

that would bear fruit within a year and a half.

National media attention contributed to the project's early

growth. On September 3, 1979, another lengthy article in the Times coinciding

with the fortieth anniversary of the German invasion of Poland and the start of World

War II was accompanied by photographs of a taping session. One benefit of such

coverage was that it attracted the involvement of individuals and organizations across

the United States and abroad. A faculty member from the Hebrew University in

Jerusalem and a member of the Israeli Knesset joined the project's advisory board.

Concerns about the long-term financial viability of the

project were allayed by a major grant from the New Haven Foundation, a local philanthropic

institution. Three members of the New Haven Jewish community were instrumental

in securing the grant: Geoffrey Hartman, a professor of English and comparative

literature at Yale, whose wife was one of the first four interviewees and who himself

had become a member of the project's board of directors; Albert Solnit, a professor

of pediatrics and psychiatry at Yale; and Malcolm Webber, the director of the Connecticut

Anti-Defamation League.

Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock turned their attention to refining

the process of drawing witnesses out, enabling them to tell their stories.

Although taping was always done in a safe place, a setting in which people would

feel free to let memories emerge, there also had to be a sympathetic listener who

knew how to be unobtrusive, nonjudgmental, and encouraging, all at the same time.

This trusted listener would intrude with questions as little as possible, using just

a few words and gestures to elicit each survivor's story. Moreover, as in the

first taping session, the listener would never appear on camera, so there would be

no distractions for the viewer, no reactions on the face of the interviewer to suggest

any sort of attitude toward or evaluation of the survivor's story. Then and

only then could the past be revealed and dealt with, and witnessing could itself

become a historical event, filling the gap in the historical record.

At its best, the process of giving testimony was the creation

of a narrative in which the inconceivable trauma of the survivor was finally externalized

and known by both speaker and listener. The listener was an indispensable participant

in the process, respecting both speech and silence, serving as the empathetic other

that many survivors had despaired of ever finding.

Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock thought they would hear stories of horror and atrocity.

They did, but that was only a part of the truth. Events and images were often

presented in fragmentary, undigested form, with the survivor barely a part of the

narrative. It was as though these imprints had been preserved unchanged and

secluded from the stream of daily conscious life, like nightmares, and the survivor

wanted literally to force them onto the listeners in order to rid himself of them.

But beyond the anguish and dread, and invariably superseding them, was the intense

yearning to make contact, to be connected with the truth of one's life.

Testimony: Between Total Engagement and Historical

Evidence

As witnesses to the testimonies, Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock

were asked not only to be totally engaged during the interviews, but also to be a

future presence in the lives of the survivors as guardians of their truth, to be

people they could think of or come back to and feel known. The trusted listeners

became part of the survivors' relentless efforts to rebuild lives in which past and

present are connected and continuous while at the same time their differentness and

uniqueness are preserved. The passion for authentic contact was also reflected

in the relations between Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock and their relations with others who

came to participate in the project, often reaching a level of intensity that was

hard to bear or to integrate into the flow of everyday life.

Ms. Vlock received personal phone calls for more than a

year after a two-day recording session in Palm Beach, Florida, in which she had interviewed

more than fifteen survivors and had developed close ties with the social workers,

the volunteer hostesses, and the local camera crew. Many of them obviously

felt that a special relationship had been established. Dr. Laub recalled days

in which he participated in as many as five interviews and experienced a need to

do something different, to escape the bonds created by sharing atrocities and the

anguish and injury they caused. He would jump into a cold swimming pool to

regain his composure, and he wondered whether this was akin to the ancient Jewish

ritual of cleansing oneself of contamination.

So radical was the project's departure from established

procedures of historical research that, even as it began to bear fruit, it encountered

skepticism and sometimes resistance from members of the scholarly community, particularly

historians. Scholars were not prepared to deal with a medium that went beyond

the printed word, transmitting not only what the survivors had to say but also their

faces and gestures, pauses and outbursts, hesitancies and determination to tell their

stories. This demeanor evidence introduced a whole new element demanding interpretation,

challenging both the scholarly and the casual viewer. It also added a new dimension

of credibility to Holocaust testimonies: not surprisingly, a recent study has

shown that the believability and persuasiveness of a speaker's message are based

in large part on visual and vocal factors such as facial expressions, gestures, and

tone of voice.

Some historians objected to obvious inaccuracies in survivors'

accounts of long-past events. One such inaccuracy arose when a survivor spoke

excitedly of seeing four chimneys explode during a failed uprising at Auschwitz.

At a subsequent meeting of scholars, it was pointed out that only one chimney exploded;

Dr. Laub replied, in defense of the survivor, that her testimony was psychologically

true, affirming a deep but long-buried and unexpressed sense of the possibility of

resistance to extermination. Ms. Vlock encountered another type of insensitive

skepticism, the complaint that the testimonies were repetitive: transport in

a cattle car, separation at the concentration camp gates, slave labor, death marches,

and so forth. Insisting that each survivor had a singular story to tell, one

that could not be duplicated, she herself became repetitive on this point.

Expanding Throughtout the United States and Beyond

Nonetheless, the first group of four taped interviews had such

an impact when shown to various groups and the press that it gave the project a momentum

which has never been lost. Between the initial taping sessions in 1979 and

the establishment in 1981 of a permanent home for the ever-expanding collection at

Yale University occurred a period of rapid growth of participation by survivors and

support by individuals and philanthropic institutions.

Taping sessions were held outside New Haven in other Connecticut

communities during the summer and fall of 1979. An attempt to secure the participation

of the leadership of the Hartford Jewish community succeeded, primarily because survivors

saw the various newspaper articles and were receptive to the ideas and aims of the

project. A series of meetings with the Hartford Jewish Federation Endowment

Committee resulted in taping of testimony by the survivors, with technical support

from Connecticut Public Television. Ms. Vlock subsequently produced a documentary

that was shown on the Hartford public television station as part of a Federation

fund-raiser. Contributions poured in immediately after the telecast, and the

expressions of appreciation by Federation leaders established a pattern that was

to be repeated in other cities: federation or private donor support, contact

with local social workers and psychologists, collaboration with television stations,

and press coverage, all leading to participation by a cross section of survivors

in the community.

In November, Ms. Vlock began videotaping in Israel with

the endorsement of Dr. Yitzak Arad of Yad Vashem, the official institution for the

commemoration of the Holocaust. She also traveled to Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia,

and Hungary to get a sense of the places that had been home to the survivors with

whom she was now closely involved. Visits to the sites of concentration camps

at Dachau and Mauthausen were part of this trip. A Yale student journal subsequently

published an article about Ms. Vlock's journey and her activities in the Holocaust

Survivors Film Project, and the article led to a meeting with the author and humanitarian

Elie Wiesel, who was giving a series of lectures at Yale that semester. Conversations

with Mr. Wiesel were a profoundly inspiring experience for Ms. Vlock.

In 1980, the videotaping effort in New Haven intensified, and recording

was carried on in various cities along the east coast, including Bridgeport, Connecticut;

Boston; Palm Beach; and Norfolk and Virginia Beach, Virginia. In addition to

conducting interviews, Ms. Vlock and Dr. Laub found themselves being called on to

help others begin similar projects. They also recruited and trained a corps

of volunteers to assist in their efforts, many of whom became deeply and permanently

involved in the gathering of testimonies.

The same year saw Laurel Vlock serve as co-executive producer

and host of a one-hour television documentary about survivors. "Forever

Yesterday," a collaborative effort with WNEW-TV in New York City, received an

EMMY Award in 1981.

Finding a Permanent Home for the Testimonies at Yale University

Taping of survivors' testimony continued in 1981: a notable

expansion of the effort were the sessions held in New York City in July and August.

At the same time, events of great importance to the future of the growing video collection

were occurring in New Haven. Contacts over the preceding year and a half with

various members of the Yale administration and faculty led from advice on grant proposals

to the establishment of a formal relationship between the university and the Holocaust

Survivors Film Project. It was announced on February 13 that the tapes would

be housed in the Sterling Memorial Library, where they would be catalogued and made

available to researchers. As part of a development fund drive for Yale's nascent

Judaic Studies program, a million-dollar endowment would be sought for the video

tape collection. Co-chairman of the fund drive was Geoffrey Hartman.

The formal transfer of the more than two hundred tapes of the Holocaust Survivors

Film Project to the Yale University Library took place on December 17; the collection

was renamed the Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale at its inauguration

on October 1, 1982. Later,

as the result of a major contribution, it became the Fortunoff Archive.

Later,

as the result of a major contribution, it became the Fortunoff Archive.

Even as the institutional life of the collection was beginning,

the work of Dori Laub and Laurel Vlock was continuing to expand. Meetings were

held in May and June 1981 with representatives of the Canadian Jewish Congress to

help them begin their own government-sponsored video project. In June, Ms.

Vlock co-anchored with the veteran CBS correspondent David Schoenbrun broadcasts

on public television from the  World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, a historic

event taking place in Jerusalem when she interviewed, among others, famed survivor,

Prof. Elie Wiesel. She also produced About the Holocaust, an educational documentary

commissioned by the New Haven school system and later accepted for national distribution

by the Anti-Defamation League. Most important, Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock continued

to participate in the process of recording testimonies as it expanded throughout

the United States and Canada and into Israel and Europe.

World Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, a historic

event taking place in Jerusalem when she interviewed, among others, famed survivor,

Prof. Elie Wiesel. She also produced About the Holocaust, an educational documentary

commissioned by the New Haven school system and later accepted for national distribution

by the Anti-Defamation League. Most important, Dr. Laub and Ms. Vlock continued

to participate in the process of recording testimonies as it expanded throughout

the United States and Canada and into Israel and Europe.

The original meeting of Dori Laub and Laurel Vlock was fortuitous,

but it resulted almost immediately in a unique collaboration that has borne fruit

of inestimable value. Nineteen years after the Holocaust Survivors Film Project

was established, its historical and moral resources are only beginning to be tapped.

As the years pass, the details of individual stories may get lost in the minds of

those who listen to them, but the message of each testifier and act of testimony,

the connection established between past and present, dead and living, evolves with

more and more clarity, a clarity that no one could foresee during the experience

of testifying.

With the thawing of the Cold War, there is a chance for

the reconciliation of nations and peoples over large parts of the globe. Such

reconciliation cannot be achieved, however, without a clear and open understanding

of the past, especially the period before the Cold War. Faithful records of

that past are contained in survivors' testimony. Just as thousands of survivors

have taken advantage of the opportunity to repossess their long-hidden childhoods,

so nations can find here important materials for reconstructing their own former

selves and building a better future.